NEPAL - A Natural History Trek

by Dr. Martin Griffin

Reprinted for the October 1970 Sierra Club Bulletin

Last year I was asked to plan and scout a natural history trek in Nepal in preparation for a trip to that area in 1970 and a Sierra Club 1971 Outing. This was an intriguing assignment, which I promptly accepted, because the Himalayas along with western China harbor the world’s greatest concentration of rhododendron species. Perhaps a springtime trek could be timed to witness their successive glorious blooms at different elevations against a backdrop of 24,000-foot peaks and ice fields.

I have long been involved in wildlife protection and felt that any survey of Nepal should include the Terai on the Indian border where the last of Nepal’s rhinoceros and tigers are found. Here, as in the middle Himalayas, I expected to find a vast variety of birds at the height of their springtime courting and nesting activities.

Nepal is a year-long crossroads for bird migrations from Europe and other parts of Asia. For example, many species of birds from regions as far north as Siberia migrate south into India in the autumn by skirting the Himalayas on either end, following the valleys of the Indus and Brahmaputra rivers. In the spring, they return through Nepal, directly over the crest of the Himalayas, perhaps driven by instinct that developed before the Himalayas were formed a scant million years ago.

Some 850 species and subspecies of birds have been recorded in Nepal, so I thought it prudent to ask an expert on Himalayan birds to accompany me. I found him in the person of Dr. Robert Fleming, a missionary whose wife, Dr. Bethel, was head of the Shanta Bhawan Hospital in Kathmandu. Bob Fleming is one of those rare naturalists who knows the people and cultures as well as the diverse plants and animals of the Himalayas. He is resident ornithologist in Nepal for the Field Museum of Chicago. Also joining our exploratory trek was Howard B. Allen of Belvedere, California, a horticulturalist knowledgeable about rhododendrons, primroses and allied species.

Until twenty years ago Nepal was closed to outsiders, so vast areas have only recently started to be explored botanically. The inner Himalayas contain a wide variety of biotic communities ranging from subtropical to alpine to aeolian, a few miles apart. The latter community is the result of pockets of decomposed windblown pollen, found at 22,000 feet elevation and higher which support bacteria and mites, with the top link in this humble food chain being a small spider. As such, it is the highest and largest permanent resident on earth.

Most sensible people plan treks in the Himalayas in autumn. The monsoon rains which start about June 1 and end in early October are finished. The weather is crisp, rock climbing is safer, mountain peaks are clearly visible.

Springtime trekking, we found, was another matter. Masses of cold air from the snow fields colliding with thermals from the hot plains of Nepal caused brief but violent winds which flattened our tents the first two nights out. Each year haze tends to build up in the valleys starting in March but clears every week or so with a tremendous electrical display off the peaks. With the lightning there is a little rain and wet snow above 12,000 feet. At our lower elevation camp on the edge of the Trisuli gorge the rain activated a few blood-searching leeches. They were quickly forgotten as fireflies hatched and made the evening magic. The patter of light rain on dry ground also brought out winged termites by the millions. Some were attracted to the kerosene lamp on our dinner tarp where they mated and instantly dropped their wings, crawling away to start a new colony.

On the basis of our survey, we planned a tour and trek for eighteen people in the spring of 1970 that took us by elephant, landrover, air, but mostly by foot, from the Indian border of Nepal to the southern border of Tibet. As the jungle-crow flies, we traveled only about 100 miles, from an elevation of 400 feet in the rhino country of swamps and jungle to fields of scrub rhododenron at 13,000 feet, near the crest of the Himalayas. We decided to stay below this level not only for practical physiological reasons, but because the richest plant and animal life is in the forests and fields between seven and eleven thousand feet.

Our headquarters for the tour was Kathmandu and its valley, comprising 250 square miles at four to five thousand feet elevation in the midlands of Nepal. The valley itself contains a surprising variety of wildlife and rich cultures dominated by a peaceful blending of the customs and shrines of Hinduism and Buddhism. Lord Buddha, a notable defender of wildlife, was born in Nepal in the Terai.

Just outside our hotel window in Kathmandu we saw huge fruit bats hanging by day in a tall pine tree; swallows flew at eye level along dirt streets searching for hatching insects, and vultures clustered in the trees near the burning ghats at the edge of town. Dr. Fleming has seen 250 species of birds in the Kathmandu valley alone, and I was surprised at the number of hawks, kites and eagles we saw on one bird walk, indicative of a healthy food chain for these raptors. At our Godavri camp on the edge of the valley we visited a village where primitive life has remained unchanged. Rice was being husked in foot-operated ricemills which made a high-pitched clink at regular intervals. This sound is heard throughout the rice growing areas of Nepal and curiously is almost indistinguishable from the call of the Crimson Throated Barbet, a large bird of the foothills.

Hindu New Year’s celebrations featuring ancient fertility rites coincided with our visit. Actually, fertility is a year-round theme in Nepal as erotic extravaganzas are painted on temple exteriors. To counter the rampant fertility in the face of gradual control of malaria, smallpox, and tuberculosis, family planning is now being cautiously introduced by the government. We saw billboards in remote areas advocating a family of two children.

Our scouting trek introduced us to the immense wildlife conservation problems of Nepal. These ate related to an excess of people, over half of whom live in the mountainous regions and nearly an of whom are subsistence farmers and graziers. There is a rapid population growth of the present 11 million people in Nepal estimated at 2.5 per cent per year putting increasing pressure on marginal lands and wildlife. The average population density is nearly 200 per square mile which is high considering that 40 per cent of the entire country is composed of permanent snow and glaciers and steep rocky slopes in the Himalayas. The good intentions of the World Health Organization to eliminate malaria with DDT in the jungle Terai, a river valley containing tropical forests and swamps, has set off a chain reaction of unanticipated events which may lead to the complete destruction of its commercially valuable Sal, Shorea robusta, forests, the conversion of big game habitat to pasture, and the end of one of Nepal’s greatest economic assets, the National Wildlife Refuge. Because they are no longer endangered by the deadly malaria of the lowlands, farmers from the mountains are relocating in the jungle Terai.

Near Tiger Tops lodge in the heart of the refuge, we were astounded by the encroachment of herds of domestic water buffalo. These animals are driven across the Raptie River in the morning at places clearly marked “sanctuary” and returned at dusk. On the backs of the herdsmen and their families are huge loads of leaves cropped from the forest trees to serve as fodder. The low-lying areas where trees cannot grow support great meadows of l5-foot tall elephant grass which provide essential food and cover for rhino, tiger, boar and a host of other wildlife. This habitat is being gradually replaced in some areas by low turf grasses through burning, trampling and grazing by domestic cattle.

There are wardens in the refuge with orders to shoot game poachers on sight, but they seem helpless against the more insidious pressure from local graziers and tree croppers. The possible fate of the refuge can be seen across the river, once richly forested, where there are endless shimmering vistas of sun-baked soil barely supporting a mantle of low grasses.

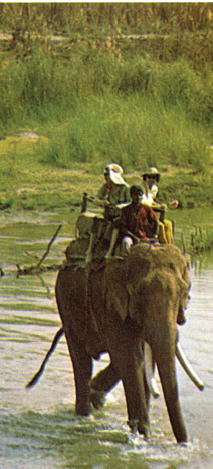

To reach the National Game Refuge in the Terai we travelled by air over a very rugged range of terraced mountains. Landrovers met us at the tiny Meghauli airstrip and drove to the banks of the Rapti River where we mounted elephants for the long ride through jungle to Tiger Tops, a rustic lodge built on stilts. Our party was entranced by the beauty and variety of plants and wildlife. In three days on elephant back and in landrover we saw 163 species of birds and flushed a dozen or more rhino. We did very little walking as an encounter with a baby rhino and its mother while we were on elephant back convinced us that bird watching by foot was indeed risky.

The area of the Himalayas we chose for our wildlife and rhododendron trek lies northwest of Kathmandu, in the upper watershed of the Trisuli River. Our trail followed the east side of the Trisuli River gorge on an ancient trade route to Tibet. The geology of the still rising Himalayas was readily seen in the deep river-carved gorges, the streams carrying glacial silt from high ice fields. There were numerous rock slides from unstable slopes where house-sized boulders showed sedimentary striations laid down when this was a sea bed in Precambrian times.

Adding greatly to the enjoyment of the trek were the personnel recruited by Col. James Roberts of Kathmandu. They represented three ethnic groups. . There were sherpas, a tribe of Tibetan stock from the Mt. Everest region who handled logistic and camp details; one problem-the packing of 1,000 fresh eggs with which we started the trek. Our 36 porters were chiefly boys and young men drawn from the mountain Tamang tribes, and Newars, an indigenous tribe of the Kathmandu valley. One evening at campfire in a small meadow at 10,000 feet, surrounded by massive displays of rhododendrons in full bloom, they entertained us with sinuous tribal dances and melancholy songs.

Having hiked in the silence of the high Sierra, we were surprised and delighted with springtime songs of both humans and birds of the Himalayas. Tamang boys tending an animal or terrace-field yodeled little mountain melodies back and forth across chasms or played a wooden flute for their own enjoyment. The resemblance of the minor key melodies to the calls of Himalayan birds was unmistakable, especially the “I told you so” song of the Indian Cuckoo.

We passed several trading parties from Tibet composed of men and women. They wear their long hair in braids and have mongoloid features similar to American Indians with whom they share common ancestors. Their flat faces, formed by large nasal cavities, are an adaptation that permits them in freezing weather to warm the air they inhale. They were light-hearted and gregarious people and a peek into their packbaskets almost always revealed roots and tubers of mountain plants. These were valuable commercially and were to be traded for supplies in Kathmandu. At least 14 different roots of wild plants have medicinal importance in Nepal, some of which are claimed to prevent goitre, an extremely common affliction. In the Himalayas many other wild plants are used in some manner.

A major source of animal fodder is a band of evergreen oaks (Quercus semicarpifolia) extending nearly the length of the Himalayas between the six and eight thousand-foot level. Barefooted herdsmen moved high in these trees lopping off leaves and small branches with their sharp curved kukris knives. This practice has drastically altered the ecology of these oak forests and its related insect and bird life; the oaks are no longer dominant, other species are pressing in or land is turning to high desert.

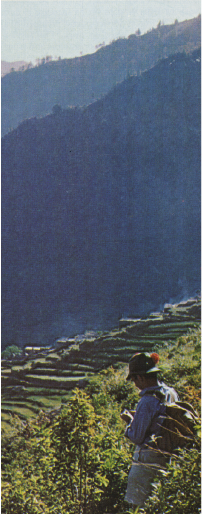

The watershed of the upper Trisuli River and its tributaries, some of which arise in Tibet, is a vast area of about 1,000 square miles. Four years ago His Majesty’s government, primarily concerned with siltation into a hydroelectric dam that serves Kathmandu, undertook a study and demonstration project of the watershed with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Agency. The watershed is divided into two areas, a southern portion which has a very high density of population. Here, terrace farming of corn, barley, wheat, and millet has spread everywhere up to 7,000 feet. The forests have been completely removed, except on the steepest slopes. Now even these areas and higher are being subjected to overcutting for firewood, overgrazing, burning, and leaf cropping. As a result, erosion and massive landslides of the already geologically unstable soils are occurring and floods and siltation are aggravated downstream.

The goal of our trek was the more remote, northern portion of the Trisuli watershed. It is sparsely populated and contains wild areas and great forests, still relatively unscathed. This area includes parts of the Langtang and Ganesh Himal, nearly 24,000 feet high with perpetual glaciers, and the dramatic Gosainkund Range, sacred to Hindus and Buddhists. Ganesh is the elephant-faced god of the Hindu faith. Instead of turning east into the Langtang Khola tributary which has been the locale of several botanical expeditions, we headed west near the Tibetan border into seldom-visited Gatlang Valley. Gatlang, we learned, means goitre, a most appropriate name for this valley with its iodine-poor soils. At the 10,000 foot level, facing the snow plumes of double crested Langtang Himal and Mt. Everest eighty miles beyond it, we set up a base camp in a magnificent three-tiered forest of Himalayan hemlock, (Tsuga dumosa) maple, bamboo and rhododendron.

The contrast from the previous day was enormous. In order to cross the Trisuli River we had dropped down to the border village of Syabrubensi, only 5,000 feet above sea level. Here I treated the head man for malaria, a fairly common disease in these interior sub-tropical valleys. On a huge rock outcrop there was a botanical curiosity: both native palms and pines were growing side by side. This rock, larger than Gibraltar, would have been an appropriate symbol for imperial England when its dominion extended from “palm to pine.” A large prickly plant also grew in these low Himalayan valleys which reminded us of a cactus (there are none in Asia); it is a relative of the poinsettia called euphorbia. There were kapok trees in this valley which we had last seen in the Terai, and fragrant bauhinia, a tropical tree with an orchid-like flower smelling of vanilla we had admired in Hong Kong.

Two things especially make springtime trekking in Nepal worthwhile. First are the cuckoos; these large parasitic birds, who lay their eggs in other’s nests, call back and forth along the trail in April and May, the rest of the year they are silent. The haunting, often wildly distractive call of each species, of which we heard five, is never forgotten. The Great Himalayan Cuckoo says “Oh-poo-poo-poo” like someone pounding on a hollow drum. Altogether, we saw 100 species of birds on this trek. Himalayan birds generally are larger than our Sierran birds; their colors and patterns more striking; and their calls are especially distinctive and loud to bridge the great distances. In the upper forests and scrub of Gatlang valley we flushed native chukar and pheasant. Large magpies with foot-long tails flitted through the hemlocks; laughing thrushes laughed, and the nutcrackers similar to ours jawed at us. The greatest thrill came when we saw a pair of Spiny Babblers engaged in noisy courting activities. Nepal with all its birdlife, has only one species indigenous to it-found nowhere else in the world. This is the Spiny Babbler, so rare and so exciting to ornithologists (the world over) that anyone who has seen it becomes a member of the exclusive Nepal Spiny Babbler Club. The Smithsonian Institution organized a great expedition to learn about this bird, but the first nest was found and observed by Bob Fleming on the Trisuli River.

Second are the old plant friends one sees along the trail. Many of the favorite varieties in our gardens originated in the Himalayas and were dispersed to the world by early British botanical explorers. At the 7,000 to 9,000 foot level one sees daphne, clematis, rhododendrons, wintergreen, pyricanthus, berberis, cotoneaster and the magnificent Pieris formosa with reddish leaves and large clusters of creamy bell-like flowers.

There are two other intriguing plants, poisonous or unpleasant to animals, that are indicators of serious overgrazing in the Himalayan meadows. These are stinging nettles which our porters cautiously gathered every evening with wooden tongs and boiled into a nutritious soup. The other plant is Cannabis sativa, known as hemp or marijuana which grows wild and, we discovered, has a pervading tomato-like odor when we pitched our tent in a meadow of it. The rough, dried stems and leaves are sold legally in Kathmandu and are called Ganja.

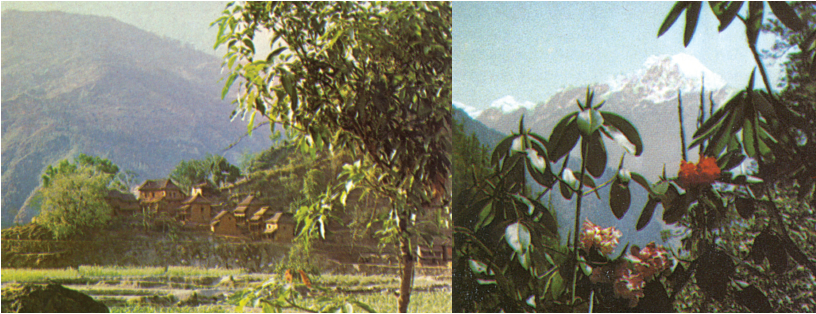

The glory of a Himalayan spring are the rhododendrons, blooming successively from lower elevations to high, starting in February and ending on the alpine scrub after the monsoons have started in June. In a wet year such as 1969, blooming occurred about one week later than the dry spring of 1970. There are no azaleas in the Himalayas, their niche being filled by different rhododendron species. The largest, the tree rhododendron (R. arboreum) was seen along the trail starting at 6,000 feet on north-facing slopes. Some of these gnarled giants reached five feet in diameter and seventy-five feet in height; there were red, white and pink varieties. Our base camp was located in a low forest of Rhododendron barbatum, a species which has a stunning scarlet flower and soft barbs on’ its stem, from which it derives its name. Its trunk was smooth and madrone-like. It formed grotesque forests about twenty feet high shaded by graceful Himalayan hemlock, often six feet in diameter. The most attractive rhododendron, we agreed, was the lavender bell-shaped flower of R. campanulatum which we found in full bloom in small forests draped with lichen on the edge of grazing meadows called “alps” at 11,000 feet. They were associated with the great silver fir of the Himalayas, Abies spectabilis. Above this elevation on a knife-like ridge, at the head of Gatlang Valley where a little-used trail leads across wild valleys to the Annapurna country, were species of pungent scrub rhododendron in snow banks at 12,000 feet. Nearby were birch and willow and a few of the Himalaya’s most westerly larches, a deciduous conifer.

While the upper Gatlang Valley is only sparsely populated – by Nepalese standards – by friendly, primitive herdsmen with their flocks, we saw unmistakable signs that these awesome forests may well disappear in a generation – while adding little or nothing to the economy of Nepal. The forests belong ‘to the government of Nepal and herdsmen pay a small fee for using them. However, there is no supervision of grazing practices and we observed herds of goats (tails up) and sheep (tails down) moving through the forest like locusts, consuming every conifer seedling and even armed shrubs. Those they could not reach were lopped over by the herdsman with his kukris. To increase grassland we saw where many small fir and hemlock had been girdled and fires set in the buttresses of larger trees. Sadly, the small primary schools we visited along the trail teach little about the magnificent natural heritage of the Himalayas to their barefoot students. The textbooks read by these children, whose future depends on the conservation and wise use of their remaining forests and precipitous farmlands is more oriented to urban life with unreal scrubbed children in black shoes peering from the pages. As elsewhere in the world Himalayan mountain children suffer from a lack of relevant education.

There are proposals being made to create an Alpine National Park in Nepal. Surely the forests of the upper Trisuli watershed would make splendid inclusion providing the activities of graziers could be controlled or eliminated. From personal observation over the past two years I predict that if Nepal can save its remaining forests and wildlife the number of visitors who come to see these wonders will far exceed those who choose to climb its noble peaks.