The Story of Bugs Cain

Friends often ask Marty: why are you obsessed with saving so much open space, rivers, and coast in California?

I have lived here for eighty-five years and witnessed the cherished landscapes of my boyhood gobbled up by witless developers and relentless population growth.

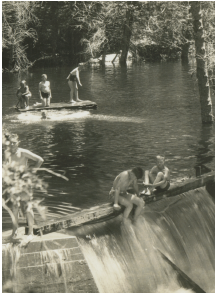

I had the good fortune to explore many of the state’s rarest gifts of nature with the Oakland Boy Scout naturalist “Bugs” Cain, a Stanford-trained entomologist. I can see him now driving the council’s big yellow bus, binoculars at the ready as we drove down gravel roads of the unspoiled Salinas River, alive with birds and swarming with insects. (No silent spring then.) We explored the Big Sur, the Little Sur, and the north coast wild rivers. We labored over High Sierra passes, climbed the White Mountains to the bristlecone pines, suffered across Death Valley, through the great valley of central California alive with vernal pools, wildflowers, birds of every species galore.

I served as Bug’s assistant during my high school and college years. We worshipped nature in the magnificent sugar pine forests on the south fork of the Stanislaus river. There under the towering sugar pine we sang, “O come to the church in the wildwood, come to the church in the vale….” We would run after him when he saw a favorite plant or bird. He excited the Boy Scouts with his knowledge and wit.

I’ll never forget the Yosemite Valley Firefall with the moon over Half Dome. He whistled

“Indian Love Call” in perfect harmony with my girlfriend, Buggs Clark, at Camp Curry’s

campfire.

I saw the best of wild California before World War II, and I cannot let go of any opportunity to save nature along with the help of the wonderful naturalists and friends I have known over the years.

More about Bugs and the Dimond Camp

The mecca of Boy Scouts in Oakland was Dimond Camp in the lower Oakland Hills. It was in the Sausal Creek watershed, forested with old growth redwoods. (Mike Dimond was a settler in the late 1800s who lived at the head of the present Fruitvale Avenue.) Alluring trails led off through nearby Joaquin Miller Park and through the Skyline Redwoods into the urban wilderness of the new East Bay Regional Parks.

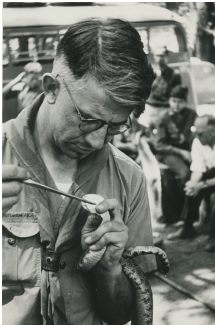

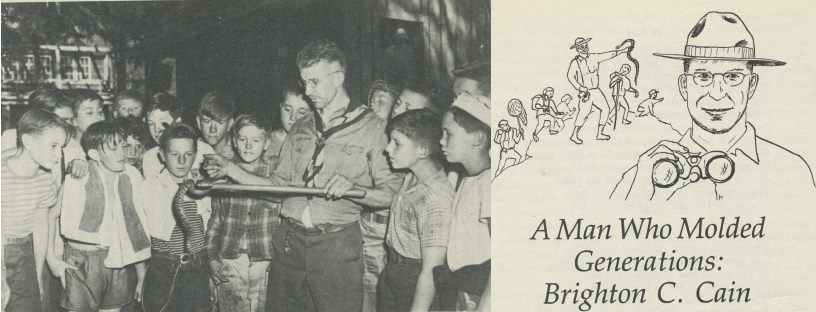

The Bug House was the house of wonders, combining elements of museum, mini-zoo, classroom, planetarium, and window outlook on the feeding station. No boy ever emerged the same. Bugs could persuade city boys to accept snakes and insects, study the way of a bee with a flower, thoughtfully finger a rock, and watch birds and game without wanting to grab or scare.

Cain’s leadership of boys at urban parks, college campuses, or bay shorelines, his repertoire of bird songs and calls, and his techniques of snake display stamped him as a colorful, effective leader and teacher. His talents imparted a deep appreciation of the natural world and instilled in boys a sense of social ethics and keen powers of observation and communication.

In 1950, amid claims that the camp use was shrinking, the Oakland Council of the Boy Scouts decided to sell Dimond Camp to the Oakland school district. No longer could city boys hike or take a local bus from their homes to camp.

The memory and spirit of Bugs Cain were perpetuated by the Rotary Nature Center (established in 1870, the oldest wildlife refuge in North America) with it’s B.C. Cain Memorial Library and the natural science center in Lakeside Park.

Protecting Sausal Creek

Friends of Sausal Creek are a group of residents, teachers, students, merchants, and elected officials working together with the City of Oakland and County of Alameda to restore the Sausal Creek watershed. The Friends Vision Statement expresses the group’s hope of creating an intact riparian corridor from the hills to the Bay that’s accessible to all.