THE WILD GRANDEUR OF KIPAHULU

In February 2000 Dr. Griffin lectured on “Preserving Open Space on Maui” at the Maui Research & Technology Center. He cautioned, “You can’t afford to lose another inch of your coastline to development.” The state now has an effective Hawaiian land trust. Today Hawaiian Islands Land Trust continues to conserve land at an increasing rate.

In 1968 Dr. Griffin was a member of a scientific expedition that laid the groundwork for the Kipahulu Valley’s inclusion into Haleakala National Park (including the Seven Sacred Pools on the Maui coast). Below is his article about that exploration.

THE WILD GRANDEUR OF KIPAHULU

reprinted from HONOLULU, A Topical, Tropical Magazine, November 1968

This Hidden Maui Valley is Incredibly Beautiful, Full of the Rarest of Bird and Plant Life.

Here is the Story of a Jungle Expedition as Told by Dr. Martin Griffin

Remote Kipahulu Valley near Hana, Maui is the site of a historic month-long exploration by a team of scientists last year. They hope that this area may in part be preserved as a wilderness linking the Haleakala National Park with the ocean. The author, Dr. Martin Griffin, a physician-conservationst and expedition member, wrote the following account partly from his field diary.

WET AND TIRED, I descended from above Base Camp II in Kipahulu Valley on the southeast slopes of Mt. Haleakala. For the past 10 days I had been privileged to be part of an expedition of scientists studying one of the last remaining areas of true Hawaiian wilderness, and one of the few untrodden places on the earth where evolution of plants and animals has taken place – often with spectacular results – with no disturbance by man.

There’s no place on earth quite like the Kipahulu Valley. In the short distance of six incredibly difficult miles, ranging from the dry, cold subalpine crater rim at 7,000 feet to the “tropical paradise” of the Seven Sacred Pools at sea level, I had passed through a wide variety of plant and animal habitats. Here, in cloud forest and rain forest, I saw scientists soggily engaged in studying soil, climate, plants and creatures.

Their findings have convinced The Nature Conservancy, which sponsored the expedition, and the National Park Service, which partly financed it, that the upper Kipahulu Valley must be preserved in all its wild grandeur. Access will be limited to those qualified to use it without harm. The lower portions of Kipahulu stream, which pass through the superlative Seven Sacred Pools to reach the sea, will be developed for recreational use.

The preservation of gems such as Kipahulu doesn’t just happen, however, as Hawaii well knows. Conservationist Laurance Rockefeller made the first move to save Kipahulu two years ago when he purchased, for more than $500,000, the critical 58 acres on which part of the Seven Sacred Pools are located. This brought The Nature Conservancy, a non-profit conservation organization, on the scene, for Rockefeller said he would donate his holdings to a park concept if the Conservancy could acquire the remaining 10,000 acres in the Kipahulu valley. The Conservancy, under the direction of Western Regional Director Huey Johnson, quickly obtained purchase options on all privately owned parcels. Some of the land is being gift-deeded to the Conservancy by Mr. and Mrs. Hamilton McCaughey, owners of the Kipahulu Cattle Co., if other parcels are purchased, and Hawaii’s Governor Burns has indicated willingness to dedicate a 10,000-acre state-owned portion of the valley to a wilderness park.

The Nature Conservancy has now exercised its options and must raise a total of $592,000 by public donation if all the pieces of this complex project are to be pulled together and the Valley of the Seven Sacred Pools Park becomes a reality. More than 500 gifts have come from Hawaii residents and several hundred from the Mainland. So far $240,000 of the $590,000 needed is in hand. Contributions are still urgently needed.

PART OF KIPAHULU VALLEY IS a tropical rain forest. In fact the 3000-foot level may be one of the wettest spots on earth which may explain why the expedition found no trace of humans having lived in this valley and why it had never been explored nor penetrated by trails. Steep coastal cliffs have kept the Kipahulu district isolated and have saved the Kipahulu Valley from logging of its koa trees and clearing for grazing which has destroyed so much of the virgin lowland forests of the rest of Maui and the other islands.

When these cleared areas are abandoned or neglected, the native forest doesn’t return; instead such imported pests as guava, gorse, wattle and eucalyptus move in, furnishing no food or shelter for native wildlife. A tortuous dirt road and a one-party telephone line serve the 15 families of Hawaiian descent in Kipahulu and its neighbor village of Kaupo, but its people have entered the 20th century with Jeeps and television while retaining their friendly, unhurried way of life.

In mid-July of 1967, The Nature Conservancy employed Dr. Richard (Rick) Warner of Berkeley, a tall, husky biologist and veteran leader of other expeditions, to lead a monthlong expedition into Kipahulu to see if it harbored unknown scenic treasures as well as rare and endangered native Hawaiian birds, plants and insects.

In less than two weeks Dr. Warner organized his expedition. First he flew to Maui to develop a plan of operation with officials of Kipahulu Cattle Company Ranch. The company supplied Kipahulu Schoolhouse, a remnant from sugar plantation days, as base for the expedition and assigned five young Hawaiian cowboys, under the direction of Jack Lind, the manager, to cut trail, a formidable task. It was decided that three camps would be established at 3,100, 4,100 and 6,500-foot levels, on a sharp ridge which divided the valley in half and which ran nearly to the top of Mt. Haleakala. From these camps side trails would be cut to explore the valley floor. Supplies would have to be carried by backpack. The top camp was located so that the field party could hike up over the crater rim on its last day, spend the night in the crater, and descend the ancient Kaupo Gap trail in time for a celebration luau, old Hawaiian style with a buried wild pig.

Next, Dr. Warner flew to Honolulu to discuss projected studies with scientists who would at various times join the expedition. I was signed on as physician and photographer. On August 1 I arrived at Hana, looking very different from the lei-bedecked passengers bound for Hotel Hana Maui. I was equipped with mountain tent, medical equipment and an insulated, waterproof picnic basket filled with cameras, film and dessicant to hopefully keep things dry. My 35mm Pentax camera invariably became as wet as I during the day and during the night I dried it with body warmth in my sleeping bag. In spite of this miserable treatment, it performed admirably. High speed Ektachrome film gave beautiful color in the very dim but even light conditions of the rain forest.

• • •

I WAS MET IN HANA by Dr. Milton Howell, a general practitioner who has served this isolated community of 1,300 persons for six years. He is co-chairman of the Valley of the Seven Sacred Pools project. His son, Robert, later joined the expedition as assistant to Dr. Warner. The next morning I met Harry Hasegawa, expedition provisioner, who operates third generation Hasegawa’s General Store at Hana. It has all the sights and smells and clutter a general store should have, plus a catchy tune which plays several times a day, titled Hasegawa’s General Store, now a popular Island song.

Dr. Hampton Carson, professor in the department of entomology at the University of Hawaii, joined me August 2 for the drive down the twisting one-lane coastal road to Kipahulu. Dr. Carson is a geneticist specializing in the evolution of the fruit fly whose scientific name is Drosophila. He said that over 400 honest-to-goodness species have been described in the islands .. There are marked differences between the islands based upon geography. Maui and Molokai have many common species, while there are many species on Hawaii not found on Maui. There is a difference, he suspects, in species between the two sides of Haleakala and this trip may prove it. Thus these isolated islands, with their great number of Drosophila species, provide an opportunity found nowhere in the world to study the workings of evolution.

At tin-roofed Kipahulu schoolhouse one room was filled with mountains of gear. residing over the organized confusion was Rick Warner in khakis and rakish beret. Cowboys turned backpacker were tying 35-pound loads wrapped in waterproof black plastic. There was no shortage of manpower. The five families of Scottish, Portuguese and Chinese-Hawaiian descent that run Kipahulu Ranch have had 50 children among them. Jeeps arrived with Hawaiian women and wide-eyed little boys to see the first trip up the mountain. (Where do they hide their daughters? )

• • •

DR. CARSON AND I decided to go up the mountain that day. We drove by Jeep through meadows dotted with mango thickets and healthy Herefords. Ahead we could see Kipahulu Valley which made a sharp turn to the west before it ascended to the crater rim. Behind us was the cobalt Pacific with foaming reefs. At about the 1,500-foot level, the dense forest started and the meadows abruptly ended. Here we shouldered heavy packs and started up the steep ridge leading to Camp 1 – four hot, tiring hours away.

Halfway we dropped down a steep incline to a stream lined with fern and had a drink from a trickle of tepid rust-colored water. A week later some of our party had to swim and use ropes to cross this same stream. We found Camp 1 located in a swampy plateau. Jack Lind and his trail-cutting crew, who had already been on the mountain 10 days, were snugly situated in a tent and were cooking boiled rice and chili over sterno stoves. We sensed an approaching storm and quickly erected my mountain tent on a platform of tree fern logs, driving the pegs into the soft wood. The jungle night – humid, soundless and black – overtook us under the dense forest. Hamp and I had barely finished dinner when the rain started as if someone had thrown a bucket of water in our faces. We dove for the tent and for the next 12 hours were treated to the most spectacular drenching rainstorm imaginable. A bucket holding 10 inches of water filled up and turned over. Our platform of pula logs rose slowly during the night as the swamp filled, and when we got up to adjust guy lines we sank nearly to our knees. But our ship held tight. The rain staccato on the rain-fly, a scant foot from our ears, and the crashing of lightning off the peaks (unusual for Hawaii) made sleep impossible. Then we became aware of a gradually increasing roar from the valley. Dormant waterfalls on both sides of the valley were draining the swampy highlands and thundering into the valley floor.

As soon as the storm stopped, Hamp was out collecting specimens. To attract fruitflies from decaying vegetation, he used Gerber’s banana baby food fermented with yeast from the Lobelia shrub, Clermontia. He spread the sour-sweet mixture on a branch and collected the flies in tubes with food and mold inhibiter in them. Hamp’s motto was “bring ‘em back alive” to his laboratory in Honolulu where the pregnant female flies reproduce.

Hamp was ecstatic about this site with its uncut koa forest sheltering a bewildering variety of native plants. He knew of no other place on the islands still intact and at such a relatively low altitude. Within a few hours he had four new species and eventually found six. He also found the spectacular Drosophila parkinsi, probably the largest Drosophila species in the world with a wingspread of some 22 mm.

• • •

ON AUGUST 5 the main body of scientists arrived at Camp I and the trailcutters moved to Camp II to make room. The new arrivals were Dr. Andrew Berger, chairman of the department of zoology of the University of Hawaii and an expert on native Hawaiian birds; Dr. Charles Lamoureux, a professor in the department of botany who, with his assistant, Robert De W Reede, would make a reference collection of the native plants of Kipahulu; and Dr. Nixon Wilson, from the Bishop Museum, charged with general entomology and particularly the study of the parasites of mammals and birds. Among those to arrive later were William Ho, expert on mosses; Winston Banko, authority on rare Hawaiian birds at Hawaii National Park, and Garrett Smathers, who would map the different soils and vegetation cover from sea level to crater rim.

The next day, I was treated to a delightful botanical introduction to the wealth of native plants and their Hawaiian lore by Dr. Lamoureux. Altogether, he and his assistants collected more than 200 species of higher endemic plants in lapahulu, plus 75 species of ferns, lichens and related plants. We admired the tangled climber ieie with spectacular yellow and red bloom which was used as framework on feather capes. The handsome shiny-leafed pelea, named after the volcano goddess, has some 50 species characterized by a lemon or licorice odor when the leaf is crushed.

Through the forest we saw several other flowering shrubs in full flower. One was a hydrangea cousin called broussaisia with umbrella-like clusters of flowers and berries on which, we discovered, the amakihi bird depends for food. Everywhere was naupaka with its incomplete white flower symbolizing separated lovers. Clermontia, with fig-like fruit, was always above us, for it springs from the fallen trunks of other trees.

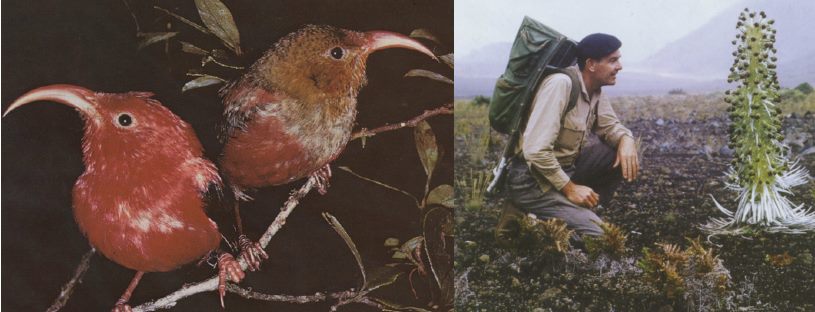

Perhaps the most beautiful flower of the rain forest was the tremato lobelia. Its single stem, often four feet tall, was crowned by four large horizontal sprays of long tubular pink flowers. The trip was worthwhile if only to see this plant etched against the waterfalls of the opposite pali; and even more incredible to see the iiwi, a brilliant crimson honeycreeper bird, dipping its long curved orangered beak with extensible hollow tongue into the curved corollas. Thus bird and plant are linked together by evolution.

A botanical and ecological misfortune that Hawaii is only beginning to realize is the large number of species of world famous woody lobelias, unique to Hawaii, which have become extinct in recent years. At one time Hawaii had 130 or more species. Some 17 different species of these remarkable giant plants were found in Kipahulu valley by Dr. Lamoureux and his staff.

The acacia koa forms the canopy and is the dominant rain forest tree up to the 3,500-foot level. Our first camp was located in probably the most magnificent remaining forest in the islands. The koa gives the forest a Japanese water-color mood, with its huge twisted branches and Scimitar leaves. Its foliage changes a different shade of green with every shift of mist and sun. Elsewhere it has been heavily logged. The other conspicuous middle story tree of this rain forest is the olapa (cheirodendron), looking like an aspen with leaves rustling in the slightest breeze; ferns dominate the under story.

With each plant collected, the altitude and location were carefully recorded. Also Bob De Reede started a daily record of rainfall, air and soil temperatures and soil acidity. Humidity ranged from 90-95 % saturation of air with water-very high indeed!

Dr. Warner, our leader, started his project of determining the extent of bird malaria on the mountain. It is thought that when the night-feeding culex mosquito was introduced to the islands in 1826 from the water tank of a whaling ship, it spelled doom for all the native Hawaiian birds below the 2,800-foot level where culex thrived. They had no immunity to avian malaria spread by culex and were gradually exterminated by this and other introduced diseases, along with loss of their habitat.

Dr. Nixon Wilson set out battery-operated light traps for insects at various elevations. On birds collected by Dr. Warner, he deftly searched the skin and flushed out the nasal passages with saline for tiny mites. The mites on native Hawaiian birds had never before been described.

Our luck ran out on August 7. A Kona storm was approaching that would deluge the entire island but we had a few dry hours before it struck. We decided to use the lull to explore the valley floor on a trail previously cut. In about two hours we picked our way straight down through the dense vegetation of the 500-foot pali, gingerly using roots, ferns and rotting logs for hand and foot holds. Finally, the Kipahulu Valley floor! Truly atropical jungle. Beneath the koa canopy were great expanses of matted staghorn fern, often taller than a man.Here the trail ended and Rick andI decided to extend it across the valley floor to the opposite pali, about a mile distant. We were well aware of the danger. If it rained hard the streams we crossed would become impassable.

Rick and I alternated cutting trail with a machete through the fern tangles. We passed through bogs up to our calves where it took great effort to pull out a boot. We were thoroughly wet from the steady drizzle. Carefully we blazed trees on both sides as we went, to find our way back, as the staghorn fern quickly springs back and trails disappear. To get lost on this valley floor would be ridiculously easy and was the main peril of the expedition.

By now the rain was harder but we pushed on to the final stream, the largest in the valley. With incredible luck we had struck a major waterfall, 250 feet high, hidden by foliage from aerial photographs. We hung out over the gorge to admire the three-tiered falls and the hanging tropical gardens nurtured by the spray. Our antics disturbed a pair of white-t~iled tropic birds, far from the sea, and they wheeled off, crying. The scene was overwhelming in its wild beauty and I like to think we were the first humans ever to see it.

We retraced our steps and quickly crossed the rising streams, not relishing a night here chilled and hungry. Two thirds of the way up the vertical pali to our camp we stopped to rest. The roar of waterfalls on the opposite ‘pali were now filling the valley. We counted 15 within view, some with free falls of several hundred feet from the mist that obscured the top of the cliff. Our view was framed by an ancient koa which suddenly had its yellow-green foliage bathed in sun. It was still raining in the valley and the most glorious intense rainbow appeared, lasting five minutes, arching over the waterfalls. At the end of the show, Rick and I applauded. Now the Kona storm took over in earnest. Drenching rain greeted us in camp. We gulped hot soup and tried to improve leaky tents. In the next 24 hours our rain gauge registered nine inches.

• • •

The next day Dr. Berger and I moved our gear through the rain up to Camp II and we carefully avoided the noose and bent sapling traps the Hawaiians had set out around camp for wild pig. The trail up was swampy and in places steep. At 3,500 to 4,000 feet the koa tree disappeared and was replaced by the native ohia lehua tree, a eucalyptus relative which forms forests with grotesque, tiered root systems above ground. The aerial roots are encased in a thick soft brownish-red moss in which charming little gardens of fern, lichen and many plants grow.

But the ohia lehua’s greatest splendor are its flaming red blossoms which furnish thousands of little nectar cups from which the honeycreeper birds feed. Whenever we sat quietly for a few minutes we were soon surrounded by honeycreepers singing, scrapping and feeding. The Hawaiian honeycreepers are one of the most remarkable examples in the world of adaptive radiation. Some 27 different species of these beautiful little birds have arisen by adapting themselves to special conditions and food supplies. Thus the Maui parrotbill for seed-cracking; the nukupuu with sickle bill for prying bark; the iiwi with long curved beak and hollow tongue for probing tubular il’owers. Charles Darwin might well have made his classic observations on the origin of species on Maui as well as the Galapagos Islands!

Camp II would have been easy to pass were it not for the transistor radio blaring up from the gloom of the tree fern and ohia lehua forest. Several trees around camp held great masses of the lily, Astelia, which is an epiphyte in the rain forest, but is the chief ground plant at higher and dryer elevations. This camp was set on a well drained slope to avoid the swampy misadventures of Camp I. A remarkable thing about rain forest camping is the scarcity of water held by these porous soils when it’s not raining. One hour after a deluge at Camp II we had to walk half a mile to find a cup of drinking water!

The next morning I followed the trail crew to the trail head at about 5,200 feet, in what is called the cloud forest. Directly above was the saddle at 6,500 feet, where Camp III would be located, and beyond were two high altitude lakes. The character of the vegetation was changing and trail cutting more difficult. At the higher altitudes with less rain and more wind, the ohia was becoming shorter, more dense and scrubby. Near the crater rim at 6,800 feet it disappeared and was replaced by great expanses of deschampsia, a rare native bunch-grass.

The most remarkable bird observations of the expedition were made late in July in the upper ohia forests, near Camp III, by biologist Winston Banko. For nearly two weeks he patiently searched for the Maui nukupuu, last seen in 1896, and listed as extinct by wildlife authorities. He was also searching for the rare Maui parrotbill. Finally, his patience paid off. He made three historic sightings of the nukupuu and observed at close range the big beaked Maui parrotbill. Two other endangered species, the crested honeycreeper and the Maui creeper, were trapped in mist nets, photographed and released, as were the smaller apapane and the small orange amakihi-all honey creepers.

I often think how fortunate we expedition members were to have unobstrusively observed what much of the plant life and wildlife of Hawaii must have been like a scant two centuries ago. Unbelievably, in that brief time nearly half of all the species of native birds which had existed on these islands for uncounted centuries became extinct through the hand of civilized man.

Kipahulu Valley, conserved as a wilderness park, offers Hawaii a chance to redeem in a small measure that tragic history. Let’s make certain that beneath the humid canopy of its koa and ohia forests can continue to unfold, as Darwin put it, that “Mystery of Mysteries” – the origin of new life forms.